When beginning any project there is always this moment of “oh man, what do I do first?” For the longest time I would start in the worst way possible by diving head-first into projects and working only on the parts that excited me the most. I consistently ignored the big picture in order to focus on the details. I learned a couple of things from trying to work this way for nearly a decade:

- I never finished a project working in this manner.

- I still do this and always risk failing to complete projects as a result.

- It wasn’t until I worked on defining the scope of my project that I understood what I needed to “hyper-focus” on.

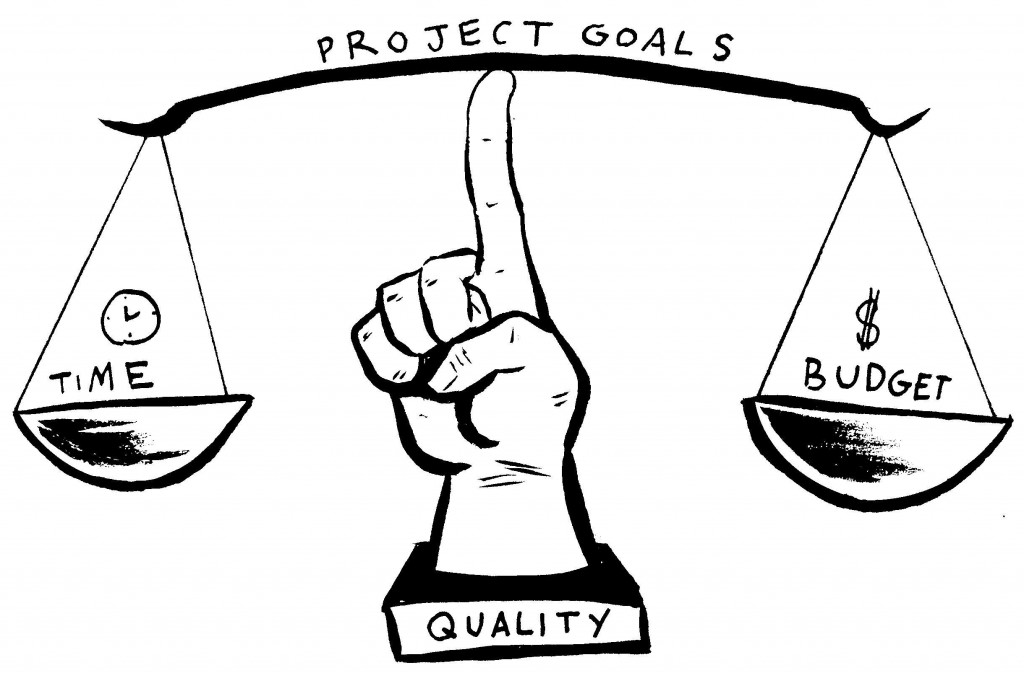

Artists tend to “hyper-focus,” losing themselves in the work. This is a great thing for productivity but it can be lethal for actually completing projects. Defining scope is all about looking at the project you want to complete in its entirety and maintaining that “big picture” perspective for the duration. The way to assess that “big picture” is to remain aware of the three separate tenets that determine the course of any project: time, cost, and quality.

Time/Deadlines

Time is a factor that must be addressed immediately. Do you have a year to finish the project? If so, how many hours a week must you put in to finish on-time? How many hours will each step take? Time management is about setting deadlines, and deadlines are all about knowing what you can accomplish and how long those things will take. Having firm deadlines can act as a catalyst to propel your growth, or they can drain you if the timeframe is unrealistic. Due to this fact, it is important to accurately determine the amount of time you will require to complete a task before committing to a specific deadline.

One of my favorite assignments to give to students is an activity called “60 Pieces in 60 Minutes.” My students get five minutes to pick sixty pieces of paper and five art implements from a communal pile. I use a large timer to count down each minute. As soon as time starts, the students frantically fill the first page and soon discover that they finish even before the first minute has elapsed. Some take longer than the timer allows. It isn’t until halfway through the activity that they start to calibrate their speed so that they finish closer to the full minute-mark. Because of the time constraints placed on them by the assignment, the students tend to grow in their ability to control their pacing and are able to complete later pages in exactly one minute.

Only after students learn to control their speed can they focus on creating quality work within the same timeframe. After that it’s a hop, skip, and a jump to mastering how to create a full comic while working more competently within time constraints.

It takes all of us time to learn this, so don’t expect to be good at it right away. No one is! But try to work on budgeting your time since it’s critical in terms of controlling the scope of your project.

Cost/Budget

There are many factors which determine the budget of a project, even if that project isn’t for commercial purposes. You may not realize it, but cost is a factor that limits the amount of work you can afford to put into things. First you need to ask yourself: how much money am I willing to sink into this new project? In terms of materials alone, there’s a world of difference in terms of the scope a budget can afford you. If you’re willing to spend only a few dollars, be prepared to work on a few pieces of printer paper with a #2 pencil and attach it to your refrigerator or Facebook wall. If you have $1,000 to spend that is a whole different ball game.

The money you will need to spend is always tough to gauge in the beginning. If you’re drawing your comic by hand the materials may never get all that expensive:

- Paper: $5-6 dollars.

- Inking supplies: $10-30 dollars.

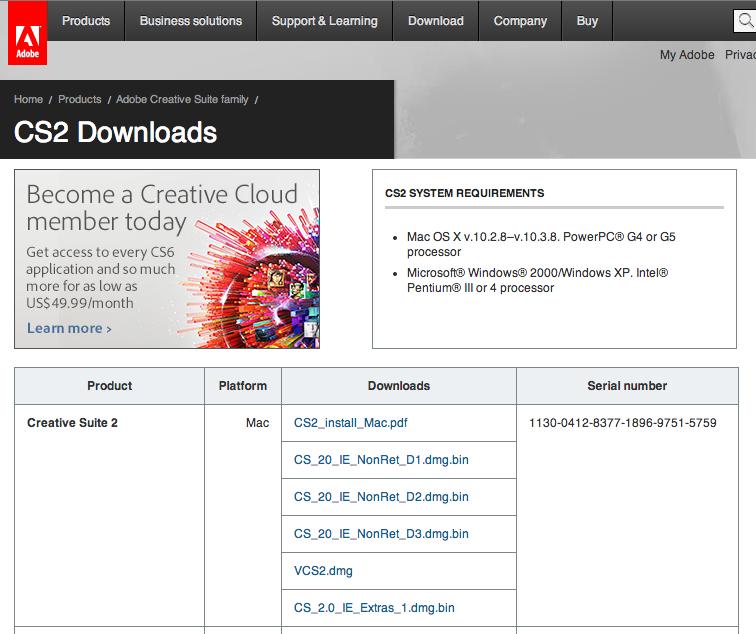

If you are going above and beyond that you may have to factor things like the cost of a computer, a scanner, and at the very least a copy of the recently released, free, Adobe Photoshop CS2.

If you’re making a webcomic, you may need to purchase a website domain for about $8-10 per month (or just get a free tumblog). And that’s the point, really. In the age of the internet, what better methods exist to distribute your independent comic to the world? The only other option would be to front the money for a self-publishing run.

If you’re making a webcomic, you may need to purchase a website domain for about $8-10 per month (or just get a free tumblog). And that’s the point, really. In the age of the internet, what better methods exist to distribute your independent comic to the world? The only other option would be to front the money for a self-publishing run.

This is exactly where I see comic artists get into trouble.

Most comic artists want their comics to be in print. We remember reading Calvin & Hobbes and Spider-Man growing up and we dream of the day that we might hold a physical copy of our own comic book. If that is the case I strongly urge you to consider, at least a little bit, the process comics go through when they reach print. If you don’t, you run the risk of compromising your art when it gets formatted for the printed page.

How many of us have seen great art look terrible in print? I know that over the course of the last decade I have seen this happen hundreds- if not thousands- of times. I can tell you that what separates amateurs from the pros is the way in which professionals plan ahead for the adaptation their comic will go through on the way to print.

I am going to write a more in-depth article on how printing directly affects composition in the future. For now, I urge you to check out Indie Publishing: How to Design and Publish Your Own Book by Ellen Lupton. This book provides a great jumping-off point for creating your project and will help you to dip your toes into the beautiful and complicated world of printing.

Cost will always be a factor that you need to wrestle with, but if you have a solid budget and plan ahead you’ll stand a better chance than the majority of creators out there.

Don’t overthink cost. One of my most successful comic projects to-date has been My Arm: the Comic. It cost me the sum total of a $50 groupon and a one hour tattoo session, the price of the pens I use to draw on my arm, and the iPad that I use to take photos of it with. That’s it. That project alone has gained me worldwide attention. I mention it only to point out that spending a lot of money on a project does not guarantee its success (compare the critical reception of blockbuster movies Titanic and Battleship).

Quality

Don’t be dismayed about the quality of your work or where you are in your artistic development. We all start somewhere. We all develop our strengths one step at a time. The experience you have at working towards your goals will help you to better achieve them. That is why I am covering quality last within this article. It’s the final element you need to focus on.

As an artist, I started out by being extremely hard on myself and my work. This lasted for over a decade. What shook me out of this was the realization that being unfairly judgemental of my work wasn’t making me better… practice and time were. What I recommend to you is simple: set clear and attainable goals at the start of each project so that you will know when it’s time to move on.

When I worked on the comic Hipster Picnic, I made it my goal to create 50 pages pages instead of holding rigidly to a time-frame for the project. Because I had no set “schedule” it actually took me two years to finish. Since I decided the project criteria was a set number of pages rather than a traditional time-frame, that gave me a way to know when the project was over.

So when thinking of the scope of your project in terms of the level of quality you expect to produce, try to be honest with yourself about what exactly it is you’re trying to accomplish. Be precise. Try not to expect a level of quality from the work that is unrealistic. As easy as it may be to “think big” or “shoot for the moon,” observing successful artists has shown me that the key is to take every project one day at a time while learning to set reasonable goals for yourself.

In the end, defining the scope of a project is about balancing three things: time, money, and quality. Your project hinges on these principles whether you know it or not. The secret to controlling these factors is to be honest about your abilities while recognizing that there are limitations to what you can accomplish. If you can work within those limitations and strive to overcome them, you will settle on a scope for your project that will allow you to be successful (however you define that).

In the end, defining the scope of a project is about balancing three things: time, money, and quality. Your project hinges on these principles whether you know it or not. The secret to controlling these factors is to be honest about your abilities while recognizing that there are limitations to what you can accomplish. If you can work within those limitations and strive to overcome them, you will settle on a scope for your project that will allow you to be successful (however you define that).

Wow, didn’t know about the C2 thing until I read this. I’m still pro Kritra http://krita.org/ or Inkscape, but until I get my PC back, I’m CS5 on a Mac. Free CS2 gives mac users a nice option because great free graphic software has been hard for me to find on OS.

Also for me, the overall cost, time, budget, and quality go hand and hand with my work schedule. I’ve been lucky to have more free time to develop art, but many times trying to budget time between school and work lowered the quality of my work. I was just too sleepy when the time finally came to draw.

One thing that helped me was when Ryan Estrada had a great idea of making 12 hour lab days, where people could get together and just do art. Bringing food together and just getting people to work on something even after a hard week, seemed to really bring out some great comics from everyone. Long term projects would then be scheduled for people in 12 hour sessions once a week. Some people even started graphic novels in the group.

The Cs2 thing definitely is game changing. Adobe has gone on record saying they didn’t offer it for free, the serial numbers were put up on the site along with the free downloads because they did not want to support the software migration of such an old model to newer hardware systems (specifically for people who had actually BOUGHT the software.)

I, along with everyone else on the internet who has a long history with Adobe, seems to understand that this move was them maintaining a stance that they are not, nor will ever be, a free software – but hey you can use this backchannel for free because we won’t be checking it. Personally I am a big believer in free and open source graphics software. I spent an entire year doing nothing in my comic creation process on any software that wasn’t free and open source. It works. I have some articles for digital coloring in GIMP coming out this month.

As for Ryan Estrada’s article, LOVE IT! I have done a lot of collaborations like this in the past. My Graphic Novel Project and I did our last comic “Denial” mostly during a 24 hour work session with about 15 people. It was the COOLEST thing ever.

I am actually thinking we should do one for Making Comics.

I have a long term Webcomic that my wife and I work on, and really… it started just because we wanted to do something together- there was no planning initially, and it’s grown far bigger than we had intended. The reality for me is that there’s ‘no end in sight’ for this project. It’s a long form comic, and it will eventually end, but I’m accepting of the fact that this end could be a decade away, that actually excites me, personally. But at the same time, I don’t want that to be the only thing I ever ‘complete’- and I struggle with this. I’ve made it a personal goal to make another comic, and to complete it within two years- but I’m so afraid that I will throw the balance of the first webcomic out of place, I fear screwing myself out of completing anything else.