In the last chapter, I compared making a graphic novel to growing a tree. When growing a tree, there are things that can kill its growth, such as drought, floods, insect infestations, etc. Just like those things that can kill a tree, there are things that can stop the progress of your graphic novel. I like to call them roadblocks because they stand in the way of your progress, and sometimes you may not even realize it. In this chapter I’ll talk a bit about these roadblocks and potential ways to get around them.

The Perfectionist Attitude

First let me bust out an Oxford American Dictionary for those of you who don’t know what a Magnum Opus is:

Magnum opus – Origin from Latin meaning “great work”. A large and important work of art, music, or literature, especially one regarded as the most important work of an artist or writer.

Why did I bring up this definition? Because I hear this a lot from comic artists and I think the magnum opus mentality is the root of the problem. Let me explain.

You don’t choose your magnum opus, your audience does. Once you stop worrying about it being the best work of your entire life and start focusing on finishing a story, you might actually have a chance of finishing a piece of work that ends up becoming your masterpiece.

When I was working on reMIND (the animated version) about eight years ago, I was having lunch with a brilliant screenwriter who said something that stuck with me. It went something like this:

“If something happened to reMIND, you could just start on another story tomorrow. Easy. You probably have tons of other ideas!”

When he said that, my mind fought it. I felt like reMIND was my life’s work. It had to work. I had nothing else! But when I thought about it a bit more, I realized that I did have other stories. I had been writing stories all my life, and reMIND was just one of them.

I had another conversation with Jim Ballantine, the producer of Ren & Stimpy who told me:

“Instead of thinking about your project as your only one, think of it as the first of twenty that you will create in your life.”

Both of those conversations shook me up, but they were exactly what I needed to hear. The idea became clear and simple in my mind as time went on:

It’s all a numbers game.

Complete the best story you can right now, and move on to the next one. Your first story probably won’t be your best one, so get over it. Think about it, the first time you rode your bike wasn’t to jump the Grand Canyon. The first time you drew a picture, you weren’t a Marvel cover artist. I didn’t win Mega Man II on Nintendo the first time I played it, but now I can beat it with one life.

Don’t get caught in the trap of redoing everything over and over, because it will never be perfect. George Lucas keeps changing Star Wars every few years even though the original was life changing for me. What you create can never be considered your greatest work until you finish it and get it out for the public to decide for themselves. Instead of thinking of it as your greatest work, try thinking of it as your greatest work to date. After all, don’t you want to make your next story better?

Finding Your Style

Many artists worry that they don’t have a unique enough style, an instantly recognizable style that’s never been imagined or created before, that will go down in the history books to be studied for generations. Okay, maybe they’re not that grandiose, but it does seem more important to most new artists than it needs to be. I know this because I was one of them, and I’ve had this conversation with many others struggling to figure out the same thing. I’ve spent years worrying about what my style was, what it should be, or could be.

One of the problems with searching for your style is that you end up only focusing on style and ignoring structure. In addition, many beginner artists end up imitating current trends thinking it’s their style. For example, in the past few years, artists have been choosing the “manga” style because it’s popular, and it keeps them from ever learning anything else. In the 90’s, I (and everyone else) tried to copy a popular Spider-Man artist’s style. All we ended up doing was showing everyone we could clone his style. A problem with copying another artists style is you tend to copy the bad habits along with the good. Most beginner artists haven’t studied enough art to know they’re making the same mistakes as the artist they’re copying.

I’m not saying that you should never imitate your favorite artist or trend. You should! But don’t stop there. Imitate many other trends and artists that you find interesting as well. Imitate the classic painters, modern artists, and sculptors that you like. Find artistic inspiration from different fields like animation, design, typography, architecture, film, comics, claymation, and 3D software. Look at artists from completely different cultures around the world.

Just as your life experience will define who you become as a person, your artistic experience will define your style as an artist. Your style is naturally a combination of everything you love, so stop worrying about it, and definitely don’t force it.

Keep Calm and Carry On

What if your idea is similar to something else out there? Should you give up on your idea? Should you continue? Over the years I’ve talked to a lot of people who started a comic book or graphic novel, but suddenly pulled the plug because they saw another comic or movie with a similar storyline. It saddens me when people abandon their dreams because they think someone else beat them to the punch. I think the only time you should stop working on your idea is if your story is finished or you don’t enjoy it anymore. And if you don’t like it, then change it so that you do.

Every artist’s style and vision is unique.

I’ve realized this more and more over the years, especially when working with amazingly talented artists in a studio. Companies spend a lot of money to keep an amazing artist because they know they can’t pay another artist to replace or recreate that artist’s style. When an illustrator becomes known for his unique vision and style, you wouldn’t pay some random artist to imitate him and expect the exact same result. If you really want to capture a style, then you need to hire the artist who perfected it.

Give 100 artists the same assignment and they will all give you a completely different result. Each artist can only bring his or her skill-set to the table. Each artist has different interests, opinions, passions, likes, and dislikes that affect what their final version will look like. So, if you have an idea for talking ponies, wizards, or giant robots, then don’t let My Little Pony, Harry Potter, or Transformers get in the way of your vision.

You definitely don’t want to write your own version of Harry Potter and sell it without J.K. Rowling’s permission, but you can write your own story about a wizard. There are hundreds of stories about wizards – all of which have their own copyright. So don’t stop working on your graphic novel about wizards just because Harry Potter exists.

It never stopped the big studios.

How many times have you seen two large studios come out with a similar movie? Finding Nemo and Shark Tale. March of the Penguins, Happy Feet, and Surf’s Up. A Bug’s Life and Antz. Armageddon and Deep Impact. Sometimes the similarities are coincidental, and sometimes it’s because a studio is trying to capitalize on a popular trend. Regardless of the reason for it happening, worrying that it’s too similar doesn’t stop them, so why does it stop us? In the end, they’re all completely different films even though they have similar characters and themes.

Everything has been done before.

Last but not least, consider this – every type of story has been written before, and you can always find arguments claiming that there are only a certain number of plots that can be followed.

In 1868, Georges Polti wrote about 36 situations in which a protagonist can get into trouble in his book, The Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations. He said he found this list in the writings of someone named Goethe, who gives credit to Carlo Gozzi, who died in 1800. Look up “36 plots” on Google if you want to know more about what these thirty-six situations are.

To narrow it down even further, consider 20 Master Plots: And How to Build Them by Ronald Tobias, originally published in 1993. He doesn’t claim these are the only plots, but it’s a pretty solid list. Once again Google “20 Master Plots” to dig deeper.

Perhaps the most common argument I’ve heard is that there are really only seven basic plots. The list varies depending on where you look, but for this argument we will just reference the seven plots described by Jessamyn West, an IPL volunteer librarian found online. She claims there are only seven plots in all of literature based on different antagonists:

- man vs. nature

- man vs. man

- man vs. the environment

- man vs. machines/technology

- man vs. the supernatural

- man vs. self

- man vs. god/religion

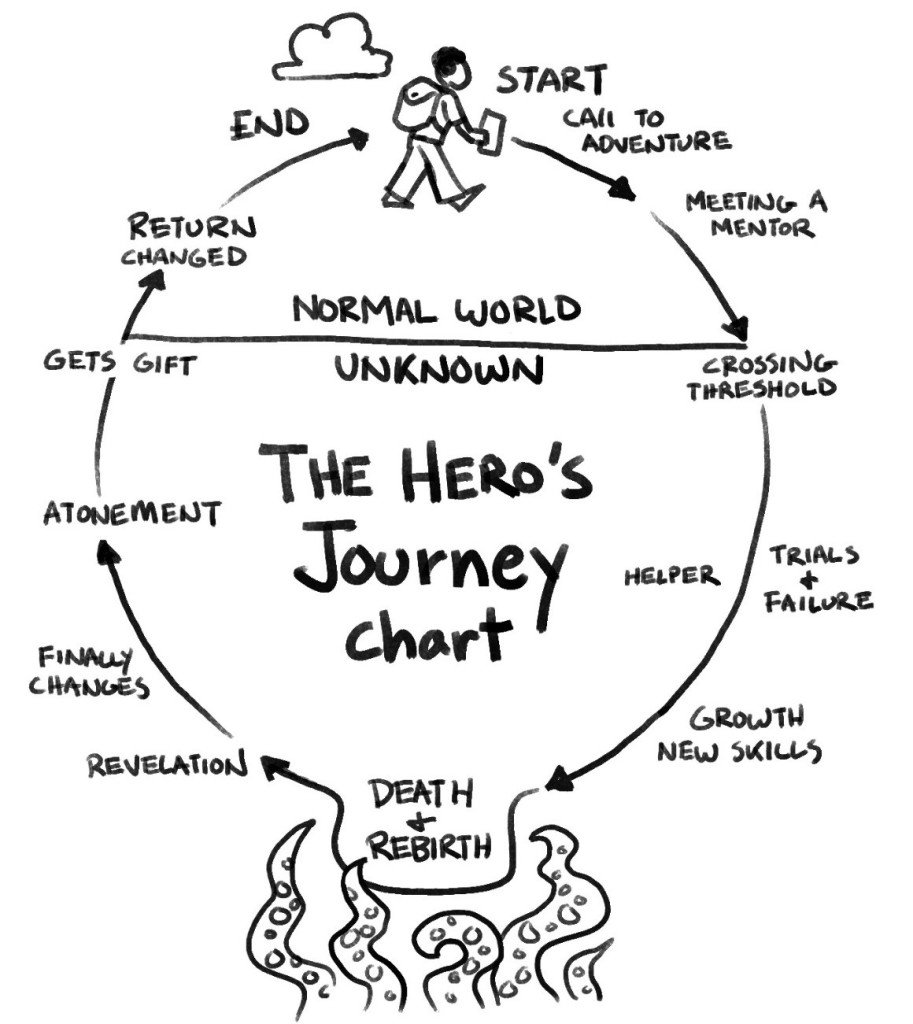

If we wanted to get nutty, we could argue that there are only three plots in all of literature, or perhaps Joseph Campbell is right in claiming every good story has the same structure in some way or another. He calls it “The Hero’s Journey” and it’s fascinating. Here’s my lame version of the hero chart.

So, if you reduce your story down to its simplest form, you’re just regurgitating the same thing that has been done a million times before. The only difference is you, your unique take on it, your unique artistic vision.

In the grand scheme of things, don’t get all bummed when you hear some new movie or comic is similar to an idea you’ve been working on for ten years. Nobody is ever going to reproduce your story the way you envision it, so relax and keep going. I almost stopped working on reMIND several times when I heard about shows with similar themes or characters in development. But then figured nobody would be stupid enough to do it the way I am. Needless to say, I kept working on it and I’m very happy I did.

I Don’t Have Time

What do you do before going to work? Anything? What do you do when you get home from work? Watch television? Play video games for hours? Get on twenty social networks and see what your closest 500 friends are doing? I’m telling you, there are millions of people who are experts at watching television because they make it their priority whenever they can. What if you replaced an hour of television with drawing or writing? What if you spent two hours focused on your goals each week night? What if you woke up an hour early and spent it sketching a page before work? I have friends who tell me they don’t have enough time, but I notice they have enough time to watch every single new television show every season. If I replaced the hours I spent watching every episode of LOST with something productive, I could have completed my biggest epic yet.

For those of you who don’t think you have the time to make a comic, I want you to try something. Make a record of how you spend your free time and add up the hours every day. Then add it up for the month, and then the year. Seeing it in writing will make you realize you’re spending an enormous amount of time on things that aren’t that important. Two hours a night on weekdays is 520 hours a year. If it takes you 10 hours to create a comic page from start to finish, you could complete 52 comic pages in a year. That’s big enough to be a graphic novel. Now that’s exciting! If you put in three or four hours a night, imagine what you could achieve. All it takes is a little reorganization of your priorities.

The secret is to just start doing it. When you see progress, no matter how little, it becomes exciting, and it doesn’t even feel like work. You’ll enjoy it more and more. Pretty soon you’ll start daydreaming about what you’re going to do that night or the next day when you have an hour to spare.

But I Have a Full-Time Job

Most people assume they could never make a graphic novel while working a full-time job. For a long time I thought the same, but now I’m convinced that having a full-time job is actually beneficial for getting your project finished. The main reason is that you have a source of income to pay your bills. This relieves the stress of worrying about paying your bills, which frees you up to have productive and enjoyable project work sessions. Nothing will kill your project like the pressure of insisting that it pays your bills.

Here is another strange thing I’ve noticed. When I was single, no kids, and worked freelance, I had a lot of free time on my hands. For whatever reason, I barely got anything done on my personal projects. But now that I’m married, with two kids and a full time job, I’ve been able to finish two massive graphic novels in my free time. So what’s going on here? I believe it has everything to do with Parkinson’s Law. It goes something like this:

Parkinson’s Law – Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.

I can definitely say that this law was in effect in my freelance jobs. In fact, I’ve had commercial storyboarding jobs in which I was given three hours to finish twenty-six frames. That amount is usually a full day of work for a storyboard artist. I was considered a fast storyboard artist in the agency that represented me, but I honestly think I was considered fast because I was the only one to accept the fast jobs. Other artists would just turn them down saying they were impossible. Any impossible storyboarding deadline would immediately get sent to me before anyone else. This was good and bad. Good, because it brought me plenty of work, but bad because they all had crazy deadlines that drove me nuts.

The invaluable lesson this taught me was simple – work doesn’t need to take as long as the status quo. I applied this thought process to all my personal projects from that point on, and because of it, I’ve been able to accomplish tons of stuff in my limited free time. If I thought a project would take a full day in a studio environment, I would give myself three hours. And guess what? I could usually get it done in three hours.

It wasn’t until I was halfway through my first graphic novel that I learned about Parkinson’s Law. I never knew there was a specific term for what I was doing, only that it worked for me. I have to admit, there’s a limit to how far it can be pushed, and if you work in this fashion long enough, you’ll be drained of all your creative juices. But I’ve learned that as long as I only apply it to my personal projects every other night, and not my full-time day job, then I can usually keep my creative tank full for when it really matters.

If you want to experiment with using Parkinson’s Law to your advantage, then here is what I suggest trying:

Set a timer.

The best way to push yourself to speed up while staying focused is to get a simple kitchen timer and put it next to your desk. Think about how long it will take to complete a small task and then set the time to half that. You’ll be surprised how many times you’ll catch yourself getting sidetracked and then noticing your time is ticking away, immediately causing you to jump back to work. Even if you don’t finish by the time the buzzer goes off, at least you’ve started training yourself to think this way.

An alternate approach is to download a timer for your computer. I found a really good one for my Mac called “Chimoo Timer for Mac” that plays one of many selectable tones at intervals designated by the user. Trust me, if you do this long enough, you will be amazed at how much work you can generate in your free time.

Just remember that work expands to fill the time available for its completion. If you give yourself the rest of your life to finish your epic graphic novel, then guess what? It will take you the rest of your life.

Afraid to Start

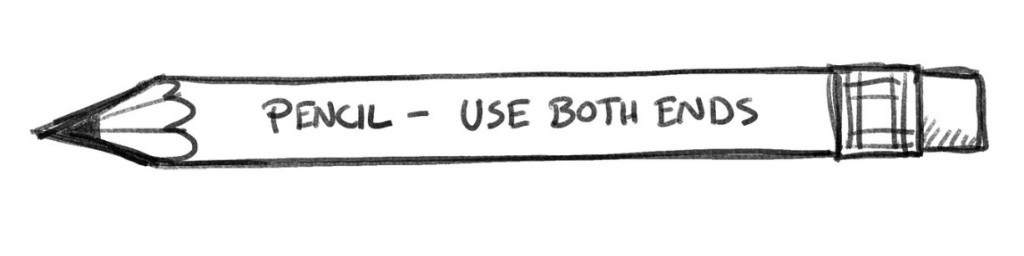

Sometimes when we’re afraid to start something it’s because we’re really afraid of failure. But when creating a graphic novel, failure needs to be your best friend because it’s a part of learning. No failure, no learning. It’s that simple. There’s a great illustration in the best and only animation book you will ever need called The Animator’s Survival Kit by Richard Williams, that looked something like this:

Instead of being bummed that you have to erase something, know that it’s part of drawing. Sure, every time you erase it’s because you made a mistake. But more importantly, it’s a chance to learn from your mistake and do it better the next time.

When I was young, I was told that in order to draw something well, I had to first draw it wrong a thousand times to learn how to do it right. I still agree with that statement today.

It’s Time to Start

Making a graphic novel is like deciding to walk thousands of miles by foot. You will never get there by just planning and thinking about it. Planning may help your journey, but until you start walking, you’ll never get closer. Are you stuck preparing for your journey with everything neatly packed and ready to go, but you just can’t take that first step? Well then, it’s time to start.

Start with this: take one of your script ideas and start thumb-nailing it out. Start drawing the first panels, then the first pages. You will mess up. You will fail. But you will learn from it. If you think your inks are bad, then make the best badly-inked page you can, and move on to the next. After you get a few pages under your belt, you’ll start to see where you need to improve, and how to fix it.

I’ve heard professional writers say that the best thing you can do to get a script written is to get the first draft down on paper, no matter how bad or disjointed it may seem. Just get it out of your head and onto paper so you can finally have something to refine. The first draft is always going to be a wreck, but you need to just get it out so you can move on to the second draft. After eight drafts, you just might have a good script.

When reMIND was in its infancy, I intended for it to be an animation short. I had no idea how to animate or write a story at that point, so I just started working on scenes. They were all terrible, but at least I finished them. Later, I learned to animate better and I reworked everything. When I did that, I learned that my story wasn’t working, so I rewrote most of it and animated it again. Then when I started the graphic novel, I threw out all my animation and started over yet again.

Yeah, I had to rework it several times before I created a graphic novel that made it to print, but I never would have finished the book if I hadn’t started it in the first place. So the lesson here is to just start and see where it takes you.

Writer’s/Artist’s Block

This feeling of not knowing what to do with your ideas can be paralyzing to the point of getting no work done. Sometimes this will happen if you have too many options floating around in your head at one time. It makes you feel stuck. It can also be because you think you don’t have any idea on where to go with your story. Regardless of the reason you think you’re blocked, I believe you really only have two options:

Option one: Take a long break. Take a vacation. Put it down for an hour, even a week, or a month. Don’t think about it anymore. Take your mind off it completely. Then one day you’ll pick it up and get so excited about it that it’ll be all you can think about. You’ll have new ideas and enthusiasm, and it’ll flow from you like a river of gold. I like this method. It’s why I like having several projects going at the same time. If I ever get burned out by one, I can jump to another that I’m excited about. That’s why I have my blog and projects like this book. It helps me when I’m burned out on drawing. This may not be the way you want to go to get around the roadblock, so the other approach is:

Option two: Just push through it. This is the discipline of being a working artist. Sometimes you have to get something done right now. If that’s the case, you just have to sit and force yourself to draw something or write something. Eventually, after making a mess of things twenty times in a row, something will finally click and you’ll start making headway again. Like I said, I prefer option one, but sometimes this is the only way to push through and get your project going.

makingcomics.com

Great article.

WOW ! Thanks Jason ! 🙂

Thank you sir. I needed to hear (read) all of it.

This is one the most encouraging blogs about making comics I have read.

Wow. Great article. Very helpful and encouraging, while staying very practical. Thanks so much!

Thank you guys! 🙂

Glad I found this. I’m on my first graphic novel and have hit some roadblocks, so this was a total score of an article to come across. Joseph Campbell is awesome, glad to see the reference. Thanks for share on the 36 situations and 20 master plots. Super helpful tips!

No worries! That’s what we’re here for!